“Sam, get up.” I heard my mom yell from the stairwell up to my bedroom on the third floor of our River Oaks house. I was confused—it felt like I’d just gone to sleep. Assuming it was time for school, I put on my khaki shorts, white polo shirt, grabbed my backpack, and went downstairs. I was nine years old.

I found my mom and my two sisters sitting on the ground with a police officer in the hallway. My uncle Bill was down the hall, leaning against the wall. My mom and sisters had tears in their eyes and were holding hands. I sat down with them and asked, “What’s going on?” I took my sisters’ hands and looked at my mom, whose eyes were bloodshot from crying. “Your dad did a bad thing tonight,” she said. “Your dad killed himself…”

My heart sank. My sisters started screaming, “No!! No!! That’s not possible!” I felt like I was going to throw up. We all began to sob. Warm tears ran down my face.

We screamed, I ran down the hallway and dropped into a ball, then ran back and hugged our mom. We all cried and screamed until we had nothing left.

It was surreal to hear that my dad had killed himself. It had to be true, but how could it be? Our dad? He was my dad. Why would he do such a thing? Didn’t he love us? Weren’t we enough? Was this a nightmare? Why couldn’t I wake up…

I screamed at my mom and at my oldest sister. “This is your fault! You weren’t nice to him! You were mean to him all the time!” My mom scolded me, saying it wasn’t true, and told me to apologize to my sister. I hate that I ever directed my anger toward her. She was only 13, dealing with her own challenges at school and with the shitty people there. I was just so angry and couldn’t understand why our dad would do this. She was at an age where everything annoyed her, including me, so I directed my anger toward her.

Later, my mom told us that a man named Mr. Tartt had come to make an offer on our house on behalf of a buyer. He warned her that the IRS was going to take the house if we didn’t sell soon. He offered $500,000—half of what it was worth. She kicked him out and called my dad, terrified that Mr. Tartt was telling the truth.

My dad received the call while picking me up from soccer at St. Francis, the school I attended at the time. It was the era of car phones with cables, and I remember him saying, “We have more time. It’s not true.” I didn’t think much of it. He dropped me off at our house on Ella Lee, then went over to his childhood home a few blocks over on Chevy Chase Boulevard, where his mother, Mossy, still lived. He went to his old room, opened the gun cabinet outside his room, took out a gun, and shot himself. In his childhood room, with his mother slept a few doors down. She’d had a stroke earlier that year and was bedridden. They had a bad relationship, which I think is why he chose that place. Later we learned the people who’d sent Mr. Tartt were the neighbors who lived across the street from my grandmother.

I remember pacing through the house. My uncle leaned against the wall, my dad’s second-oldest brother. His thick eyebrows were furrowed, unsure of how to speak to us. Other people started calling with their condolences. It was surreal. I remember talking to my dad’s friend, Thom, on the phone. We called him Uncle Tommy, though he wasn’t really our uncle. He sounded so sad. He had lost one of his best friends. I also spoke to my godmother’s son, James—whom we called Hamish. I remember he was especially sad for me, as he had lost his dad a few years earlier. I looked up to him. He was a cool twenty-something guy from New York whose dad, my godfather, was my dad’s closest friend. Hamish would die a few years later from alcohol abuse.

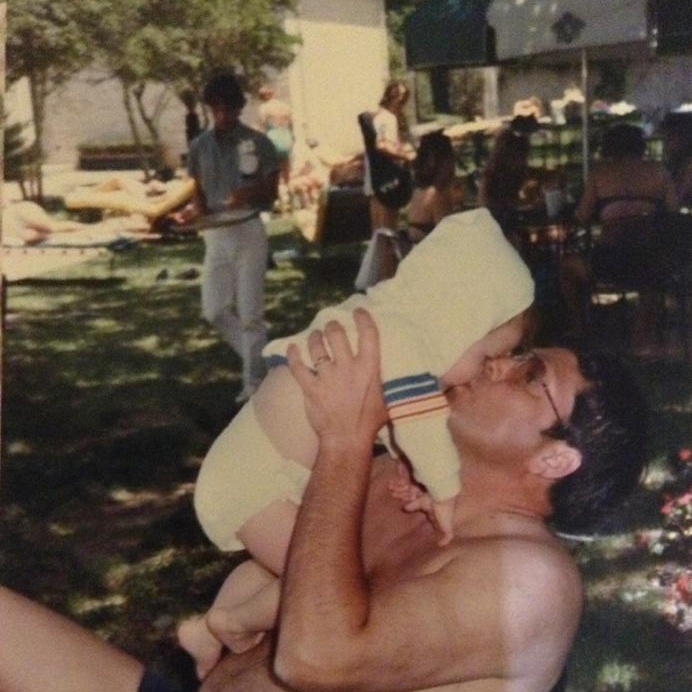

Nothing felt real. I felt like I’d been electrocuted when I heard the news. My brain was fried. How could my dad, a man who’d named me and my sister Samantha after him, shoot himself? Didn’t he know we still needed him?

I heard all the usual lines: “It’s a permanent solution to a temporary problem.” “It was selfish.” “It was cowardly.” I’ve heard people say things like that for years, and even now I hear hollow words about suicide from people who have no idea. For several years, I became a zombie. My soul had left my body. I was physically present, but my spirit hovered outside me from that moment on. Sometimes I feel it still does, watching my journey in this strange world. Despite the good in my life now, I’m always aware it can disappear instantly. I know to live in the present, but I am familiar with that pain.

I remember thanking the police officer who was there. He couldn’t help us, but it was all I knew to do. I was nine, and I didn’t know what else to do. My mom had driven to my grandmother’s house that night, after hearing from my grandmothers helper, Maurice, that my dad had shot himself. She was stopped at the scene by the police before she could see his body. It’s painful to see someone you love gone from this world. I know this from seeing my Mom’s body in the funeral home after she passed.

I can still feel the fear I felt that night. Even now, at 40, as I write this. God, it was so scary to lose my dad. I felt rudderless instantly. Even now, at 40, with both parents gone, I still feel lost sometimes.

My dad declared bankruptcy the year I was born, in 1984. He’d gone through an expensive divorce from his first wife and overextended himself with my mom, having two children from his first marriage and three from his second. He kept trying to get back on his feet, but couldn’t. When I was younger, he’d been charged with bank fraud for falsifying a loan. He didn’t serve jail time but had to pay fines with money he didn’t really have. He had our house but also debts he hadn’t told my mom about, and they hadn’t adjusted their lifestyle enough to accommodate it. Later, my half-sisters sued him, thinking he was withholding assets from them. He was already deeply broke by then.

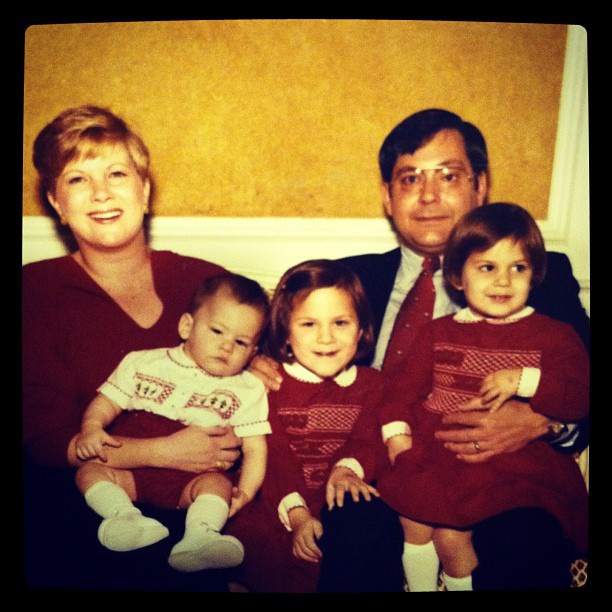

My dad’s father was a successful man but a poor father. His oldest son drank himself to death, and his youngest son took his own life. My dad was the fourth son, and none of them could ever quite fill their father’s shoes—not that their father ever really wanted them to. He fostered a competition rather than a collaboration within his family. My dad sought love by being charming, funny, and the fun one. He became a lawyer, though he’d wanted to be a professional golfer, which wasn’t allowed for him. He went to St. John’s, the Hill School, Stanford, was an officer in the Army, and then went to UVA Law. After his divorce from his first wife, he tried to get custody of his daughters, but his ex wife took them to live with her in Paris, leading to a drawn-out custody battle. Ultimately, they chose to stay with their mother. After that, he and my mom started their own family. They had my two older sisters, and then me. Shortly after I was born, my dad filed for bankruptcy.

My dad was in too deep to support so much. Only recently would I learn that he’d been going to therapy and was diagnosed with severe depression. My mom felt guilt for not changing their lifestyle enough to match their finances, but she said he kept the reality from her. She regretted turning down her parents’ offer to live in her childhood home, but she wanted her own home with my dad. Looking back, I realize how young she was—29 when she had my oldest sister, 33 when she had me. Who I was at 29 is a shadow of who I am now.

Suicide stays with you. It never fully leaves. People have said, “Get over it. It’s in the past.” I understand not wanting the past to hold you back, but the past also shapes you. You wouldn’t tell a Holocaust survivor to “get over it.” You wouldn’t say that to a victim of assault. You don’t just get over it as if it’s a bad movie. It becomes part of your story. This is part of mine.

My dad’s death shaped me more than I can express. It made me who I am—scars and all. It made me sensitive and strong. Angry and loving. Conservative and liberal. I will never “get over it.” I will simply own it. It’s who I am: the son of a father who died by suicide.

My dad’s death drives me to be the best father I can be. Now that I have a son and another on the way, I won’t ever give up on life like my dad did, no matter how scared or alone I may feel. I’d rather be poor and alive than rich and gone. And that’s a false choice. I can live a full life despite my fears and worries. I will be the father I needed when I was young.

The day my dad died, everything changed. I will never forget that terrifying night my mom called up to me. Pain and all, I keep going.

Hopefully, this gives some insight into who I am and why I’m the man I am today. I will not suffer forever. Life is too short and too important to waste.

Leave a comment